A Type of Family Strength According to Defrain and Assay (2007):

State of the Art of Family Quality of Life in Early Intendance and Disability: A Systematic Review

one

Faculty of Psychology, Instruction and Sports Sciences, Ramon Llull Academy, 08022 Barcelona, Kingdom of spain

two

Faculty of Education, University of Cantabria, 39005 Santander, Kingdom of spain

3

Group in Health Economics and Direction of Health Services, Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria Valdecilla (IDIVAL), 39011 Santander, Spain

*

Author to whom correspondence should be addressed.

Received: xi August 2020 / Revised: 19 September 2020 / Accepted: 27 September 2020 / Published: two October 2020

Abstruse

Groundwork: In recent years, there has been a growing international interest in family quality of life The objective of this systematic review is to empathise and analyze the conceptualization of the quality of life of families with children with disabilities between 0 and 6 years of age, the instruments for their measurement and the nigh relevant research results. Method: A bibliographic search was conducted in the Spider web of Science, Scopus and Eric databases of studies published in English and Spanish from 2000 to July 2019 focused on "family quality of life" or "quality of family unit life" in the disability field. A full of 63 studies were selected from a full of 1119 and analyzed for their theoretical and applied contributions to the field of early on intendance. Results: The functional conceptualization of family quality of life predominates in this area, and a nascent and enriching holistic conceptualization is appreciated. There are three instruments that measure family unit quality of life in early on care, although none of them is based on unified theory of FQoL; none of them focus exclusively on the age range 0–6 nor do they comprehend all disabilities. Conclusions: The need to deepen the dynamic interaction of family relationships and to understand the ethical requirement that the methods used to approach family quality of life respect the holistic nature of the inquiry is noted.

one. Introduction

The field of early on care (EC) is currently undergoing a meaning conceptual change. The erstwhile clinical intervention model (expert model) is at present beingness replaced by a social and transdisciplinary model (collaboration model) in which family and the surroundings are cadre dimensions [1,2]. Evolution studies accept best-selling the relevance of the social and cultural nature of human development since birth [3,4]. Still, the role that the people surrounding the children and interacting with them from their nascency and throughout their development process has been underestimated [5,6,7,8,9].

The focus now is on a positive understanding of disability and a knowledge "of the capacity for positive adaptation and of the strengths of families with children with disabilities" [10] (p. 2). Considering the positive impact that the families have in the evolution of kids with disabilities, the strategy now is to work with the families rather than working for the families [11], and to involve all the family members because what happens to any of the members has an touch on the rest of the family. Thus, it is of import to take into consideration the private needs of each of the family members as well as the needs of the family as a whole [12].

The new focus of EC on the family contributes to overcome some of the limitations that the ambulatory model had, specially regarding the time that the child tin appoint in learning opportunities and the blazon of learning opportunities that the family context offers [13]. The family involvement in plow fosters greater parental responsibility, improves family skills, and generates a higher level of satisfaction in the family [14]. Moreover, every bit Samuel et al., argue, "families that function well support societies and families with an effective quality of life are a social resource." [15] (p. 188). These are all solid reasons that support the adoption of this family model in EC, a model that has the family unit as a core dimension and whose ultimate goal is to promote a meliorate quality of family life. In fact, Bhopti et al., stated that EC services should demonstrate "positive family outcomes annually" [12] (p. 192).

Family quality of life (FQoL), then, should exist a relevant indicator of service quality [13]. The problem, nevertheless, is that in that location is no consensus in the definition of FQoL, nor information technology is easy to modify the approach and purpose of some services [2]. One of the most accepted theorizations of the concept of FQoL argues that "family unit quality of life is a dynamic sense of well-being of the family, collectively and subjectively defined and informed by its members, in which private and family-level needs interact" [sixteen] (pp. 262). This idea is reinforced past the unified theory developed past Zuna et al., according to which "[systemic factors] directly impact individual and family-level supports, services, and practices. Private-member concepts (i.e., demographics, characteristics) are straight predictors of FQoL and interact with individual—and family-level support, services, and practices to predict FQoL. Singly or combined, the model predictors consequence in a FQoL outcome that produces new family strengths, needs, and priorities that re-enter the model equally new input resulting in a continuous feedback loop throughout the life cycle" [16] (pp. 269).

This integrative and multidimensional model does not make easy to assess FQoL. The electric current evaluation methods most recognized and used internationally are the International Family Quality of Life Project [17] and the Beach Center Family Quality of Life Scale [18]. Each one has a different operational definition of FQoL and each one identifies a different number of dimensions to focus on in the evaluation—nine in the former and 5 in the latter. At a national level, in Espana there is only one musical instrument to evaluate early care services—the Spanish Family Quality of Life Scale (FQoL-S) adult by Giné et al. [19]—which only covers until 18 years of age. The FQoL-S started including seven dimensions, simply after a review of its psychometric backdrop in 2018, it was reduced to 5 dimensions. This calibration was created and developed exclusively for population with intellectual disabilities. The limitations of this instrument exercise not allow united states to know if the Spanish EC services are moving in the right direction. All of this limits us, while occupying our involvement in how to know if our EC services are moving in a meliorate direction.

The Castilian Federation of Associations of Early Care Professionals has already acknowledged that it is time to move towards a common early care model in Spain. They argued that early on intendance must exist recognized every bit a subjective right through a land law or regulation that includes all children from 0 to 6 years of age who have problems and developmental issues at some point in their development. This represents 10% of the child population of that age group, which means caring for 255,277 children in Spain in the Kid Evolution and Early Care Centers (Centros de Desarrollo infantil y atención primaria, or CDIATs).

Our systematic review was based on all the factors mentioned above together with the fact that "the evolutionary and vital circumstances of children and their families are changing and are different from those that characterize early babyhood" [2]. Our main goal was to provide answers to the following research questions:

- (ane)

-

What has been the conceptualization of the quality of life of families with a kid who has a disability or developmental concerns between 0 and 6 years?

- (two)

-

What instruments of FQoL directed to population with disability and that have adequate psychometric properties be for the child stage (0–6 years)?

- (3)

-

What are the master findings of the existing studies on FQoL in the 0–6 years stage?

2. Method

The search focused on three databases, Web of Science, Scopus and Eric, and it was based on the following keywords: "Family Quality of Life" OR "Quality of Family Life" (in English language) and "Calidad de Vida Familiar" (in Spanish). We decided to exclude the term 'disability' in our search in order to enrich our understanding on FQoL, to cover any type or diagnosis of disability and to improve our current measurements on disability related FQoL.

Our selection of the bibliographic materials was based on the following criteria:

- (a)

-

the empirical studies were based on studies with samples that included families of children with disabilities and/or developmental issues within the 0 to half dozen years phase;

- (b)

-

the studies had been published after 1999, which is the year when the publications on FQL as a social construct and extension of the QoL of individuals with IDD started;

- (c)

-

the studies were written in English or Spanish, as these are the languages used in most of the publications on this topic and the languages mastered by the authors of this article;

- (d)

-

the studies were published in peer-review journals or as book chapters.

As for the exclusion criteria, we did not consider studies in which:

- (a)

-

inability was considered a disease, since that would take entailed to discard the systematic approach in favor of the rehabilitative medical model;

- (b)

-

FQoL was studied from an individual-based perspective (instead of the holistic model mentioned to a higher place which includes all the family members);

- (c)

-

FQoL was conceptualized from a rehabilitative medical perspective, since we are interested in disability from a psychosocial approach.

In order to ensure reliability, ii contained researchers conducted the literature review and there was full understanding on their results. Likewise, two split searches were conducted in parallel: 1 focused on the scientific literature in English language and some other one focused on the scientific literature in Spanish.

3. Results

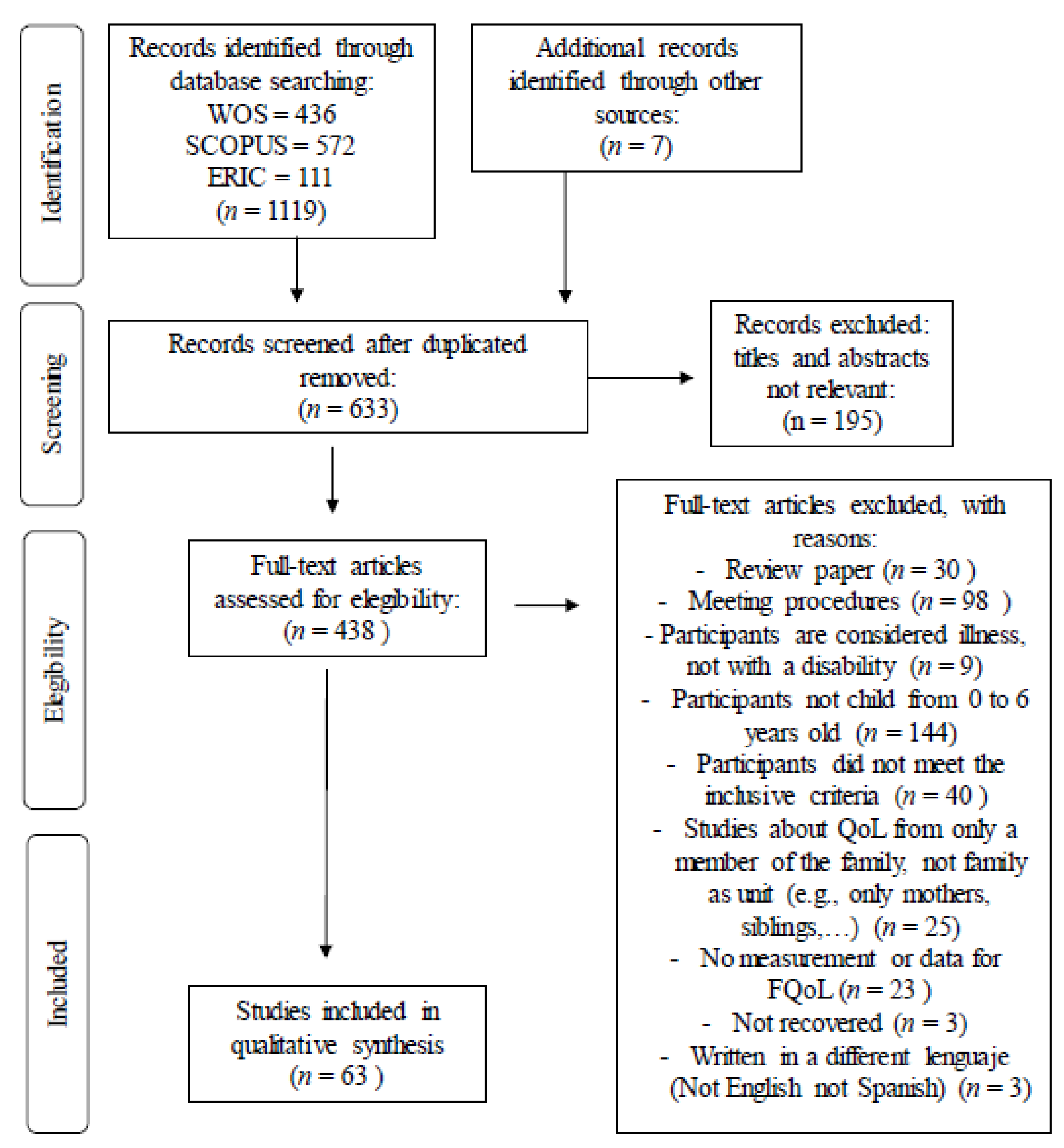

Our get-go bibliographic search retrieved a full of 1119 articles, 33 in Spanish and 1086 in English language (meet Table 1). From the 1119 articles, 493 were discarded as duplicate materials and seven more publications were incorporated from additional sources. The breakdown of these seven publications is as follows:

- (one)

-

iv theoretical studies, which provide definitions of FQoL [xvi,20,21,22];

- (2)

-

the Family Quality of Life Survey (FQOLS-2006) [23] conducted by an international squad of researchers;

- (3)

-

the study by García Grau et al. [24] published months after the searches were conducted;

- (iv)

-

an empirical study [25] found as grey literature.

The implementation of the inclusion and exclusion criteria reduced the total choice of articles to 663 records. Of these, 195 studies were removed afterward reading the titles and abstracts. After reading the total text of the remaining 438 records, 375 articles were as well discarded. The reasons for their exclusion are included in the flowchart below (encounter Figure 1). Thus, the final number of articles in which our systematic review is based is 63, from which 60 are written in English and 3 in Spanish.

The selected manufactures were analyzed and classified according to the three research questions mentioned above.

iii.one. The Conceptualization of FQoL in the 0 to half dozen Twelvemonth Stage

Considering the 63 articles reviewed, 2 ways of addressing the conceptualization of FQoL have been identified: (1) how it has been theoretically defined (Table ii) and (2) how it has been measured or operationalized (Table 3). Hu et al. [27] chosen this second approach "functional" because it identifies the areas or domains of family life that are measured through scales or other instruments. This Systematic Review (SR) follows Hu'southward functional approach.

iii.one.1. Theoretical Conceptualization

Being aware of the dissimilar conceptualizations of FQoL is an important pace in the field of inability because "it is difficult to accelerate in any field if a definition of the concept or phenomenon studied is not commonly shared and if in that location is doubt about what, in the first identify, is supposed to be measured" [31] (p. xix). The existing definitions of FQoL are included in Table 2.

From a chronological point of view, the showtime definition was formulated in 2000 past Turnbull et al. [22] cited by Park et al. [28]. This definition includes the perceptions of family members, and for this reason some authors call information technology "subjective conceptualization" [32,33]. The influence of this conceptualization in the FQoL literature is relevant [34,35,36,37].

Four years later, in 2004, Chocolate-brown and Dark-brown [xx] identified three components in FQoL. According to them, families experience quality of life when they (a) strive to accomplish what they want; (b) are satisfied with what they have achieved; (c) feel empowered to atomic number 82 the life they desire. 10 years later, these components were too included in some other report by the same authors, which highlights how the FQoL construct "changes a trivial over time in response to our understanding of other related concepts, changing social values and norms and cultural and environmental conditions" [21] (pp. 2195).

In 2010, Zuna et al. [16] proposed a definition that highlights the dynamic meaning of the construct. This definition has been cited by 15 of the articles selected in this study [half dozen,33,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49].

3.1.two. Functional Conceptualization

From the operational or functional indicate of view, the FQoL is understood as "a global upshot of services" [50] (pp. 204). At first, the conceptualization of the FQoL was based on the one used in the field of the individual QoL, which led to the consideration of the FQoL as a multidimensional construct. Indeed, researchers of FQoL accept focused on identifying the dissimilar domains that constitute the FQoL construct through the cosmos and validation of measurement instruments.

Table 3 shows the domains that plant the instruments created to implement the FQoL construct, including the name and number of domains in each proposal. There are half dozen functional conceptualizations so far. Although the number of domains in each of the proposals varies (from 9 domains by the FQOL Survey-2006 [17] to three of the FEIQoL [24]), the following domain names are repeated: family unit, supports and fiscal.

3.ii. Instruments that Mensurate the FQoL in the 0 to vi Years Stage

The results of the bibliographic search conducted for this review show that the bulk of studies focused on the 0 to vi years phase have used international FQoL scales, which were designed for all ages, such as the Embankment Center FQoL Scale [18], the FQOL Survey-2006 [17] and FQoL-S [19]. Table four merely includes the instruments designed to be applied in children between 0 and 6 years of age.

In that location are three instruments designed to be practical in EC: (1) The Autism Family Experience Questionnaire (AFEQ) [29] for families with children with autism; (ii) ITP-Child Quality-of-Life Questionnaire [thirty] for children with immune thrombopenic purpura; and (three) the accommodation of the Family Quality of Life (FaQoL) past McWilliam et Casey to the Castilian context (FEIQoL) [24] for children with all types of disabilities.

In the search for instruments to measure the FQoL and in addition to the instruments mentioned in Table iii and Table 4, we also identified 10 studies whose main objective is the development, adaptation and/or validation of the FQoL scales (encounter Tabular array v).

As we can see, these 10 studies refer to the most international FQoL scales.

3.iii. Main Results on FQoL in the 0- to six-Year Stage

In response to the third inquiry question about the main finding of the studies on FQoL in the 0–6 years, the studies applied to this age group take been divided into two tables. The first table (Table 6) classifies 22 studies that describe, compare or relate QoL of families with young children with disabilities with other variables. The second tabular array (Table 7) shows the studies that focus on the variables that predict FQoL.

The breakdown of the results found in the studies included in Table 6 is as follows:

- (a)

-

10 articles explicitly focus on describing the FQoL in the population of their respective countries. Spain [vi,44,62] has iii studies; Israel [32,60] has two, and Australia [36], Brasil [63], Colombia [59] and Malaysia [61] have one each.

- (b)

-

Two articles [64,65] chronicle FQoL to parental stress in families with children with autism.

- (c)

-

Half dozen articles relate the FQoL to a specific blazon of disability. Brown et al. [66], for case, compared the QoL of three types of families: families with a child with Down syndrome, families with a child with autism spectrum disorders, and families with none of their members having a disability. The other 5 manufactures focus on specific disabilities, namely deafness [48], intellectual disability [32,67], autism [37] and rare metabolic diseases [68].

- (d)

-

Two manufactures prefer an ethnic perspective. Algood et al. [70] address the issue of inequity in the care of African-American families compared to other ethnicities, while Holloway et al. [69] study QoL in California among Latino and non-Latino families.

- (e)

-

2 manufactures relate the FQoL to perspectives of some of the family members. Moyson and Roeyers [72] investigated the FQoL from the perspective of the siblings of the person with disabilities. Wang et al., determined "whether mothers and fathers similarly view the conceptual model of FQoL embodied in one mensurate" [71] (pp. 977). This written report shows that at that place are no significant differences betwixt the perceptions of fathers and mothers.

- (f)

-

Two studies investigate how families describe the supports and services they receive [24,71].

Post-obit the proposal of Zuna et al. [8], the 21 studies analyzed in Table 7 identify the post-obit components: (a) systemic concepts; (b) performance concepts; (c) individual-member concepts; and (d) family-unit concepts.

Beginning, the systemic concept is integrated by iii categories: (a1) systems; (a2) policies; and (a3) programs. Regarding the offset ii categories, no written report has been identified. Every bit for the third category ("programs"), Hielkema et al. [74] studied the effectiveness of "Coping with and Caring for infants with special needs (COPCA)", a family-focused program practical to 43 families with young children at loftier gamble of cerebral palsy. The results related to the group that received COPCA prove that the FQoL improved over time.

Second, the operation concepts focus on the following three categories: (b1) Services; (b2) Supports and (b3) Practices. Vii studies focus on services (b1), and all of them bear witness that the services received past families with young children with disabilities favor FQoL [7,43,46,49,50,75,76]. Balcells-Balcells et al. [77] and Samuel et al. [75] identify an increase in parental satisfaction based on the data received by the services. Taub and Werner [49] found that both religious and secular families are satisfied with the support received from the spiritual community and the social services, respectively. 8 studies focus on supports (b2). The back up of professionals to families has received significant attending, and information technology has go one of the strongest predictors of FQoL [58,78,79]. Emotional support is better considered than applied support from both services and other breezy aids [35,41,73,76,80]. In fact, the study by Meral et al. [80] reveals that emotional support is the most important factor for the respondents. Svavarsdottir and Tryggvadottir [81], on the other hand, focus on the predictive nature of family support. Finally, because the category of practices (b3), Davis and Gavidia Payine [79] recognize the value of the family unit-centered model as a safeguard for the needs of each family.

Third, the individual-member concepts integrates the following three categories: individual characteristics (c1), demographic aspects (c2) and beliefs (c3). In the private characteristics category (c1), half-dozen articles were related to parental stress. The bulk of them focus on studying how the back up [33,79,81,82] and the information received [79,81] are predictive factors of the decrease in parental stress and, consequently, of the increase in FQoL [78]. Wang et al. [83] betoken that the efforts that parents with children with disabilities make in defending their kids generates considerable stress in them. Boehm et al. [84] investigate the human relationship between the parents' religiosity and the comeback of the FQoL.

Table 7. Predictive studies of the FQoL.

Table 7. Predictive studies of the FQoL.

| Concepts of FQoL Theory (Zuna et al. [eight]) | Authors (Year) (Chronological Social club) | |

|---|---|---|

| Systemic concepts | Systems | No records have been identified |

| Policies | No records have been identified | |

| Programs | Hielkema et al., 2019, [74] | |

| Performance concepts | Services | Balcells-Balcells et al., 2019 [77]; Epley et al., 2011 [l]; Eskow et al., 2011 [43]; Kyzar et al., 2016 [46]; Samuel et al., 2012 [75]; Summers et al., 2007 [76]; Taub and Werner 2016 [49]; |

| Supports | Boehm et al., 2019 [84]; Cohen et al., 2014 [41]; Davis and Gavidia Payne, 2009 [79]; Hsiao et al., 2017 [78]; Kyzar et al., 2016 [46]; Kyzar et al., 2018 [85]; Meral et al., 2013 [80]; Samuel et al., 2011 [36]; Svavarsdottir and Tryggvadottir, 2019 [81]; Taub and Werner, 2016 [49] | |

| Practices | Davis and Gavidia Payne, 2009 [79] | |

| Individual-member concepts | Individual characteristics | Boehm et al., 2019 [84]; Davis and Gavidia Payne, 2009, [79]; Hsiao et al., 2017 [78]; Hsiao 2018, [82]; Levinger et al., 2018, [86]; Meral et al., 2013 [80]; Vanderkerken et al., 2018 [33]; Wang et al., 2004 [83]; |

| Demographic aspects | Meral et al., 2013 [eighty]; Cohen et al., 2014 [41]; Hsiao 2018 [82]; Kyzar et al., 2018 [85]; Levinger et al., 2018 [86]; Vanderkerken et al., 2018 [33]; Boehm et al., 2019 [84] | |

| Beliefs | Svavarsdottir and Tryggvadottir, 2019 [81] | |

| Family-unit concepts | Characteristics of the family | Boehm et al., 2019 [84]; Cohen et al., 2014 [41]; Davis and Gavidia Payne, 2009 [79]; Hsiao 2018 [82]; Hielkema et al., 2019 [74]; Kyzar et al., 2018; Schlebusch et al., 2016 [87]; Taub and Werner 2016 [49]; [85]; Wang et al., 2004 [83] |

| Family dynamics | Schlebusch et al., 2016 [87]; Levinger et al., 2018; [86]; Vanderkerken et al., 2018 [33]. |

In the demographic aspects category (c2), nine articles consider as predictive variables for FQoL the post-obit factors: the age of the child with a disability [41,lxxx,83,85], the gender of the child [24,39,82], the type of disability [31,80,84], the degree of disability [80,81], the number of siblings [58,81], and the marital status of the parents [44].

Finally, in the category focused on beliefs, (c3), Svavarsdottir, and Tryggvadottir [81] conclude that the beliefs of the parents regarding the severe illness of the child significantly predicted the FQoL.

The concluding cistron of the proposal by Zuna et al. [8] is the family unit-unit concepts, which integrates two categories: family unit (d1) and family dynamics (d2). In the section on the family unit unit (d1), 9 studies consider the predictive factors of FQoL. The results show that for the most office two-parent families bask meliorate FQoL than single-parent families [62,82]; family income is predictive of better FQoL [79,82,87]; and belonging to one or another ethnic group [41,82], being role of a religious community [49] or having a spiritual organized religion [84] besides determines the level of satisfaction of FQoL. Regarding family dynamics (d2), the study past Vanderkerken et al. [33] addresses the then-called homeostatic control and suggests asking the opinions of all family unit members near the FQoL.

four. Word

The discussion is developed in the order of the research questions stated at the commencement of this review. Regarding the offset question based on the FQoL conceptualization, in that location is an incipient holistic approach, but the functional conceptualization still prevails. We volition clarify our findings in relation to two previous SRs focused on the conceptualization of the FQoL [88] and on the FQoL measurement tools, respectively. Both SRs institute that the FQoL scales lack a theoretical framework and a definition of this construct. About researchers who published their studies later these two SRs followed the functional conceptualization approach. For example, in a theoretical study which integrated the perspectives of three authors from three different research teams—Schippers, Zuna and Dark-brown—it was argued that "from the QoL conceptual development and research to date, we accept a strong sense that it is usually a number of variables across a variety of life areas working in an interrelated fashion that are essential to improving QoL for individuals and families" [89] (pp. 151). Although these authors emphasize the interrelated dimension of the different variables considered, many studies that explicitly refer to the holistic theory developed by Zuna only identify the dissimilar domains of family life just practice not integrate them in their studies.

Our SR has shown that the empirical studies arrive at dissimilar, and sometimes discordant, results. The discrepancies are based on how researchers have conceptualized FQoL, the number of the domains considered to evaluate FQoL, the methodology used (i.eastward., quantitative or mixed) and/or how many members of family unit accept participated.

We agree with Boelsma et al. [90] on the need of taking into consideration the dynamic interaction betwixt the individual and the family domains in the FQoL research. The fact that many studies refer to the holistic approach of FQoL past Zuna et al. [16] shows that this holistic agreement is becoming more than and more solid in the conceptualization of the FQoL. What Zuna's definition adds to the residue of the existing definitions (see Tabular array 2) is the dynamic graphic symbol, referring to the sense of well-beingness and the collective dimension behind the definition and evaluation of the FQoL construct, since it is based on the interaction betwixt individual and family needs [91], and among services, supports and practices.

The complexity underpinning this holistic approach does not reside in its multidimensionality just rather in its dynamic aspect. To study a dynamic reality entails understanding it from its capacity to face changes. Our understanding of this dynamic sense of family well-beingness follows Bhopti et al. [12] who emphasize how family well-beingness may modify depending on significant events in the life of the family.

Considering the second research question, based on the FQoL cess instruments, in that location are no scales developed specifically for the 0–half dozen-yr phase, nor do the developed scales address all disabilities and/or developmental concerns. The FQoL-Due south by Giné et al. [xix] covers up to eighteen years of age. The FEIQoL of García Grau et al. [24] focuses on the measurement of early on care services [44] and puts emphasis on the factor "kid functioning" [38]. These same authors [24] recognise non having conceptualized the EI as extensively as they did the other scales. This acknowledgment questions the solidity of the theoretical framework on which their conceptualization is based.

The FEIQoL calibration takes into account both the dynamic sense of the FQoL and the fact that the dynamic sense can change in the different stages of the family unit life bike. However, in the studies of these authors, the dynamic concepts mentioned by Zuna are not explicitly nowadays in the FEIQoL, except for the notion of family unit routines.

Finally, regarding the third research question virtually the findings, this SR has found that research on FQoL has mainly focused on bug related to disability and chronic illnesses in children from 0 to half dozen years of age, fifty-fifty though the FQoL is construct that can be applied to a wider typology of families (families with a kid who has not been diagnosed).

Our assay of the descriptive, comparative and correlational studies identified reveals that most of them focus on the individual concepts of the unified theory of FQoL by Zuna et al. [16]. Specifically, most of them focus on the characteristics of the individual, the characteristics of the child, and on demographic aspects.

Among the predictive studies of the FQoL, there is more involvement in the studies related to supports and services, private categories, and categories related to the family unit than in the studies that focus on systemic aspects and family dynamics. Considering the former, information technology is important to highlight that at that place are no conclusive results in relation to the variables indicated, in item to the variables related to the age and the disability of the children [32,44,67]. In that location is only fractional agreement in the studies that evidence how the FQoL of the families with children with disability in the first ii years of age is less than the FQoL of the families with children with inability from 3 years of age on [44,62]. A wider agreement is reached amid the studies that show that the greater the severity of the child's disability, the lower the caste of QoL in families [half-dozen,79,86,87]. Nosotros noticed that although quantitative studies predominate, there is an increase in others that comprise qualitative [42,63,72] or mixed methodology [35,66,67,82]. We as well identified the need of match the methods used with the upstanding dimensions of the research.

Qualitative enquiry studies are needed [42] if we desire to evaluate family unit outcomes related to experiences "that can but be explained by considering the perceptions of the family members themselves, because ultimately information technology is these subjective perceptions that determine the individual's arroyo to life and how satisfied they are with life" [7] (pp. 17). In this regard, some researchers adapt their methodologies to the participants in their research. Van Heumen and Schippers [92], for instance, use the Photovoice methodology to allow the family members to speak about the images that are meaning to them.

Finally, a few words on the ethical aspects of research in FQoL. As we know, one of the ethical requirements of research refers to the coherence between the objectives and intentions of the researchers and the results obtained. From the beginning, scholars doing inquiry on FQoL identified a trouble that presented both a practical and an upstanding attribute. Poston et al., included in their study the opinions of diverse authors regarding the demand to consider the perceptions of all family members. Withal, they soon identified a applied trouble—despite trying to involve the other members, commonly only the mother participated. From an ethical perspective, these authors consider this fact to be crucial to evaluate the realiability of the results [93]. In 2006, Wang et al., published a report in which they proposed to verify if both parents understood the QoL of their family in a like way [71]. Both the fathers and the mothers responded in a like mode, which turned out to be promising for the use of the scales in the example that but one of the parents participated. This decision prompts some researchers to include merely one of the parents in the research [half dozen,8,10,l,63,69]. Although Vanderkerken et al., argued that the perceptions of fathers did non differ significantly from those of mothers in a study in which they had a broad representation of family members [33], it is still important to investigate the affect that the participation of i or more family members has in the FQoL.

In that location are numerous studies that explicitly address the limitations of non taking into account more than one of the parents, which shows that there is an ethical concern in this regard [35,39,42,43,45,46,53,54,55,60,75,82,84]. Gardiner and Iarocci [91] indicate that in the future, inquiry on the FQoL should include the voices of the dissimilar members of the family. Hu et al., establish a connection between the holistic nature of the FQoL and the method used. To solve this trouble, Brown et al., advise that one of the parents responds on behalf of the rest of the family [66], who would thus be represented by him or her [74,87,94]. However, as Giné et al., note, in that location is no way to ensure that this instruction of responding on behalf of the family has been followed by the family representative [58]. Feigin et al. [95] empathise that the participation of brothers and sisters of the kid with disabilities, in addition to the parents, is a requirement of the systemic nature of the family.

5. Implications

This SR clearly shows that the country of the art in the enquiry of FQoL points to the ecological, systemic and inclusive vision of the family and, therefore, of the FQoL in the field of EC and inability. The inclusion of studies without the term "disabilities" as a keyword in this SR has contributed to including enriching studies on this topic and to cover whatsoever blazon or diagnosis of inability. This inclusive perspective is an invitation to all services and institutions to directly their attention to the dynamic interaction of personal and commonage needs.

Equally this SR shows, in that location is a need to develop the emerging holistic conceptualization through mixed research and to be open to methodologies that overcome the limitations mentioned above. Nosotros also need to create instruments of measurement of the FQoL that are specific to this stage of life and family bicycle from a systemic perspective.

vi. Limitations

We were not able to go access to iii studies found in the databases which were included in this review based on the title and/or the abstract [96,97,98].

7. Conclusions

Empirical studies of the QoL of families with a child with a disability or developmental concerns testify a certain inertia of functional conceptualization. Notwithstanding, an incipient holistic conceptualization has also been noted. Amid the selected articles, 3 instruments accept been identified to measure out the QoL of families with young children in the age range 0–6 years: (1) The Autism Family Experience Questionnaire (AFEQ) [29]; (2) ITP-Child Quality-of-Life Questionnaire (Barnard et al. [30] and (3) Family Early Intervention Quality of Life (FEIQoL) [24]. These instruments however do not refer to all disabilities or do not accept a holistic arroyo. Considering the main predictor variables studied hither—the historic period of the child and the type of disability—there are no unanimous or conclusive results. Later the investigation, the SR has get a State of the Art of the FQoL research, since it identifies the terminal contributions in conceptualization, and the epistemological and methodological deficiencies on the studies of FQoL. This SR identifies ii key areas for future enquiry: to deepen the understanding of the dynamic interactions of family unit relationships and to sympathise the ethical requirement of having the methods used to arroyo the FQoL respect the holistic nature of the research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.F.Chiliad. and A.B.-B.; methodology, C.F.Yard., A.I. and A.B.-B.; writing—original typhoon training, C.F.M. and A.I.; writing—review and editing, A.I., A.B.-B. and C.F.G. All authors accept read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This inquiry received no external funding.

Conflicts of Involvement

The authors declare no disharmonize of involvement.

References

- Escorcia, C.T.; García-Sánchez, F.; Sánchez-López, M.C.; Hernández-Pérez, E. Cuestionario de estilos de interacción entre padres y profesionales en atención temprana: Validez de contenido. An. Psicol. 2016, 32, 148–157. [Google Scholar]

- Federación Estatal de Asociaciones de Profesionales de Atención Temprana (GAT). La Atención Temprana. La Visión de Los Profesionales. Available online: http://www.avap-cv.com/images/Documentos%20basicos/GAT-LA-VISI%C3%93N-DE-LOS-PROFESIONALES.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2020).

- Bronfrenbrenner, U. La Ecología del Desarrollo Humano; Espasa: Barcelona, Espana, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Bruner, J.South. La Educación, Puerta de la Cultura; Visor: Madrid, Spain, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Guralnick, Thousand.J. Why early intervention works. Infants Young Child. 2011, 24, half-dozen–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mas, J.1000.; Baques, Northward.; Balcells-Balcells, A.; Dalmau, Yard.; Gine, C.; Gracia, M.; Vilaseca, R. Family Quality of Life for families in early on intervention in Spain. J. Early Interv. 2016, 38, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rillotta, F.; Kirby, N.; Shearer, J.A. Comparison of two 'family quality of life' measures: An australian study. In Enhancing the Quality of Life of People with Intellectual Disabilities: From Theory to Practice; Kober, R., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, Kingdom of the netherlands, 2010; pp. 305–348. [Google Scholar]

- Zuna, N.I.; Turnbull, A.; Summers, J.A. Family unit Quality of Life: Moving from measurement to awarding. J. Policy Pract. Intellect. Disabil. 2009, 6, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadders-Algra, Thousand.One thousand.; Hielkema, A.G.B.; Hamer, Eastward.G. Result of early on intervention in infants at very high risk of cerebral palsy: A systematic review. Dev. Med. Kid. Neurol. 2017, 59, 246–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.; Kyzar, Thousand.; Zuna, N.; Turnbull, A.; Summers, J.A.; Aya Gómez, Five. Family unit Quality of Life, Trends in family research related to family unit quality of life. In The Oxford Handbook of Positive Psychology and Inability; Wehmeyer, Chiliad.West., Ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 365–392. [Google Scholar]

- Dunst, C.J.; Bruder, M.B. Valued outcomes of service coordination, early intervention, and natural environments. Except. Child. 2002, 68, 361–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhopti, A.; Brown, T.; Lentin, P. Family Quality of Life: A Key Outcome in Early Childhood Intervention Services A Scoping Review. J. Early Interv. 2016, 38, 191–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, 50.A.; Baird, Southward.G. Effects of service coordinator variables on individualized family service plans. J. Early Interv. 2003, 25, 206–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, G.; Perales, F. El papel de los padres de niños con síndrome de Down y otras discapacidades en la atención temprana. Rev. Sínd. Down 2012, 29, 46–54. [Google Scholar]

- Samuel, P.South.; Pociask, F.D.; Dizazzo-Miller, R.; Carrellas, A.; LeRoy, B.W. Concurrent validity of the International Family unit Quality of Life Survey. Occup. Ther. Health Care 2016, 30, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuna, Due north.; Summers, J.A.; Turnbull, A.P.; Hu, X.; Xu, South. Theorizing about family quality of life. In Enhancing the Quality of Life of People with Intellectual Disabilities: From Theory to Practice; Kober, R., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, Holland, 2010; Book 41, pp. 241–278. [Google Scholar]

- Chocolate-brown, R.I.; Kyrkou, Thousand.R.; Samuel, P.S. Family unit quality of life. In Health Intendance for People with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities beyond the Lifespan; Rubin, I.L., Merrick, J., Greydanus, D.Due east., Patel, D.R., Eds.; Springer: Basel, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 2065–2082. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, L.; Marquis, J.; Poston, D.; Summers, J.A.; Turnbull, A. Assessing Family Outcomes: Psychometric Evaluation of the Beach Center Family Quality of Life Scale. J. Marriage Fam. 2006, 68, 1069–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giné, C.; Vilaseca, R.; Gràcia, M.; Mora, J.; Orcasitas, J.R.; Simón, C.; Torrecillas, A.One thousand.; Beltran, F.S.; Dalmau, M.; Pro, M.T.; et al. Spanish Family Quality of Life Scales: Under and over eighteen Years Old. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2013, 38, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, I.; Brownish, R.I. Concepts for Kickoff Report in Family Quality of Life. In Families and People with Mental Retardation and Quality of Life: International Perspectives; American Association on Mental Retardation: Washington, DC, United states, 2004; pp. 25–49. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, R.I.; Brown, I. Family Quality of Life. In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research; Michalos, A.C., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, Kingdom of the netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnbull, A.P.; Turnbull, H.R.; Poston, D.; Beegle, Thousand.; BlueBanning, Chiliad.; Diehl, Grand.; Frankland, C.; Lord, L.; Marquis, J.; Park, J.; et al. Enhancing Quality of Life of Families of Children and Youth with Disabilities in the United States. A Paper Presented at Family Quality of Life Symposium; Seattle, W.A., Ed.; Beach Eye on Families and Disability: Lawrence, KS, U.s.a., 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Brownish, I.; Brown, R.I.; Baum, N.T.; Isaacs, North.J.; Myerscough, T.; Neikrug, Due south.; Wang, Chiliad. Family Quality Life Survey: Primary Caregivers of People with Intellectual or Evolution Disabilities; Surrey Place Middle: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- García-Grau, P.; McWilliam, R.A.; Martínez-Rico, G.; Morales-Murillo, C. Rasch analysis of the families in early intervention quality of life (FEIQoL) Calibration. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2019, 14, one–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escorcia-Mora, C.T.; García-Sánchez, F.A.; Sánchez-López, Thou.C.; Orcajada, N.; Hernández-Pérez, Due east. Prácticas de intervención en la primera infancia en el sureste de España: Perspectiva de profesionales y familias. An. Psicol. 2018, 34, 500–509. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, Eastward.; Liberati, A. Revisiones Sistemáticas y Metaanálisis: La responsabilidad de Los Autores, Revisores, Editores y Patrocinadores. Med. Clin. 2010, 135, 505–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, 10.; Summers, J.A.; Turnbull, A.; Zuna, N. The quantitative measurement of family unit quality of life: A review of available instruments. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2011, 55, 1098–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Hoffman, 50.; Marquis, J.; Turnbull, A.P.; Poston, D.; Mannan, H.; Wang, M.; Nelson, L.L. Toward assessing family outcomes of service delivery: Validation of a Family Quality of Life Survey. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2003, 47, 367–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leadbiter, Grand.; Aldred, C.; McConachie, H.; Le Couteur, A.; Kapadia, D.; Charman, T.; Mcdonald, W.; Salomone, Due east.; Emsley, R.; Green, J. The Autism Family unit Experience Questionnaire (AFEQ): An ecologically- valid, parent-nominated measure of family experience, quality of life and prioritised outcomes for early intervention. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2018, 1042–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnard, D.; Woloski, Yard.; Feeny, D.; McCusker, P.; Wu, J.; David, Thousand.; Bussel, J.; Lusher, J.; Wakefield, C.; Henriques, S.; et al. Evolution of disease-specific health-related quality-of-life instruments for children with immune thrombocytopenic purpura and their parents. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2003, 25, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candel, D.; Dubois, D. Vers une définition de la « qualité de vie »? Rev. Francoph. Psycho. Oncologie 2005, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schertz, One thousand.; Karni-Visel, Y.; Tamir, A.; Genizi, J.; Roth, D. Family unit Quality of Life among families with a child who has a severe neurodevelopmental disability: Impact of family unit and kid socio-demographic factors. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2016, 53–54, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanderkerken, L.; Heyvaert, K.; Onghena, P.; Maes, B. Quality of Life in flemish families with a child with an intellectual disability: A multilevel written report on opinions of family members and the impact of family member and family unit characteristics. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2018, 13, 779–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Quiroga, D.; Ariza-Araújo, Y.; Pachajoa, H. Family unit Quality of Life in Patients with Morquio Type IV-A Syndrome: The perspective of the colombian social context (South America). Rehabilitación 2018, 52, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rillotta, F.; Kirby, N.; Shearer, J.; Nettelbeck, T. Family Quality of Life of Australian Families with a Member with an Intellectual/Developmental Disability. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2012, 56, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, P.S.; Hobden, K.Fifty.; LeRoy, B.W. Families of children with autism and developmental disabilities: A description of their community interaction. Res. Soc. Science and Disabil. 2011, vi, 49–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlebusch, Fifty.; Dada, S.; Samuels, A.E. Family Quality of Life of south african families raising children with autism spectrum disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2017, 47, 1966–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Grau, P.; McWilliam, R.A.; Martínez-Rico, G.; Grau-Sevilla, Thou.D. Factor structure and internal consistency of a spanish version of the family quality of life (FaQoL). Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2017, 13, 385–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcells-Balcells, A.; Giné, C.; Guàrdia-Olmos, J.; Summers, J.A. Family Quality of Life: Adaptation to castilian population of several family support questionnaires. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2011, 55, 1151–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.Y.; Seo, H.; Turnbull, A.P.; Summers, J.A. Confirmatory Cistron Assay of a family quality of life calibration for taiwanese families of children with intellectual disability/developmental delay. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2017, 55, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Due south.R.; Holloway, S.D.; Domínguez-Pareto, I.; Kuppermann, Thou. Receiving or assertive in family unit Support? Contributors to the life quality of latino and non-latino families of children with intellectual disability. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2014, 58, 333–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demchick, B.B.; Ehler, J.; Marramar, S.; Mills, A.; Nuneviller, A. Family quality of life when raising a kid with pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorder associated with streptococcal infection (PANDAS). J. Occup. Ther. Sch. Early on Interv. 2019, 12, 182–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskow, K.; Pineles, 50.; Summers, J.A. Exploring the effect of autism waiver services on family outcomes. J. Policy Pract. Intellect. Disabil. 2011, 8, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Grau, P.; McWilliam, R.A.; Martinez-Rico, G.; Morales-Murillo, C.P. Child, Family, and early intervention characteristics related to family quality of life in Spain. J. Early Interv. 2018, 41, 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, 10.; Wang, Thou.; Fei, X. Family quality of life of chinese families of children with intellectual disabilities. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2012, 56, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyzar, G.B.; Brady, South.E.; Summers, J.A.; Haines, Due south.J.; Turnbull, A.P. Services and supports, partnership, and Family Quality of Life: Focus on deaf-incomprehension. Except. Kid. 2016, 83, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parpa, E.; Katsantonis, N.; Tsilika, Eastward.; Galanos, A.; Sassari, M.; Mystakidou, Chiliad. Psychometric properties of the family quality of life scale in greek families with intellectual disabilities. J. Dev. Phys. Disabil. 2016, 28, 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C.Due west.; Wegner, J.R.; Turnbull, A.P. Family Quality of Life following early identification of deafness. Lang. Speech Hear. Serv. Sch. 2010, 41, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taub, T.; Werner, S. What support resources contribute to family quality of life among religious and secular jewish families of children with developmental disability? J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2016, 41, 348–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epley, P.H.; Summers, J.A.; Turnbull, A.P. Family unit Outcomes of early intervention: Families' perceptions of need, services, and outcomes. J. Early Interv. 2011, 33, 201–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliam, R.A.; Casey, A.M. Factor analysis of family quality of life (FaQoL). 2013; Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Verdugo, Chiliad.A.; Cordoba, Fifty.; Gomez, J. Castilian Adaptation and Validation of the Family Quality of Life Survey. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2005, 49, 794–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, S.-J.; Chen, P.-T.; Chou, Y.-T.; Chien, Fifty.-Y. The mandarin chinese version of the Beach Heart Family unit Quality of Life Scale: Evolution and psychometric properties in taiwanese families of children with developmental delay. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2017, 61, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waschl, N.; Xie, H.; Chen, Yard.; Poon, K.K. Construct, Convergent, and Discriminant Validity of the Beach Heart Family Quality of Life Scale for Singapore. Infants Young Child. 2019, 32, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello-Escamilla, N.; Rivadeneira, J.; Concha-Toro, M.; Soto-Caro, A.; Diaz-Martinez, X. Family unit Quality of Life Calibration (FQLS): Validation and analysis in a chilean population. Univ. Psychol. 2017, 16, xx–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivard, M.; Mercier, C.; Mestari, Z.; Terroux, A.; Mello, C.; Brainstorm, J. Psychometric Properties of the Embankment Center Family unit Quality of Life in french-speaking amilies with a preschool-anile child diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2017, 122, 439–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, A.; Isaacs, B. Validity of the Family Quality of Life Survey-2006. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2015, 28, 584–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, P.South.; Tarraf, W.; Marsack, C. Family Quality of Life Survey (FQOLS-2006): Evaluation of internal consistency, construct, and criterion validity for socioeconomically disadvantaged families. Phys. Occup. Ther. Pediatr. 2018, 38, 46–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Córdoba-Andrade, L.; Gómez-Benito, J.; Verdugo-Alonso, M.A. Family Quality of Life of people with disability: A comparative analyses. Univ. Psychol. 2008, vii, 369–383. [Google Scholar]

- Neikrug, S.; Roth, D.; Judes, J. Lives of Quality in the confront of challenge in State of israel. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2011, 55, 1176–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, K.; Brown, R.; Karrapaya, R. An Initial look at the quality of life of malaysian families that include children with disabilities. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2012, 56, 45–lx. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giné, C.; Gràcia, M.; Vilaseca, R.; Salvador Beltran, F.; Balcells-Balcells, A.; Dalmau Montalà, M.; Adam-Alcocer, A.L.; Teresa Pro, M.; Simó-Pinatella, D.; Mas Mestre, J.M. Family unit Quality of Life for people with intellectual disabilities in Catalonia. J. Policy Pract. Intellect. Disabil. 2015, 12, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, S.A.; Fontanella, B.J.B.; de Avó, Fifty.R.S.; Germano, C.M.R.; Melo, D.G. A Qualitative study virtually quality of life in brazilian families with children who have astringent or profound intellectual disability. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2019, 32, 413–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McStay, R.L.; Trembath, D.; Dissanayake, C. Stress and Family unit Quality of Life in Parents of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Parent Gender and the Double ABCX Model. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2014, 44, 3101–3118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McStay, R.50.; Trembath, D.; Dissanayake, C. Maternal stress and Family unit Quality of Life in response to raising a kid with autism: From preschool to adolescence. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2014, 35, 3119–3130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, R.I.; MacAdam-Crisp, J.; Wang, M.; Iaroci, G. Family Quality of Life when there is a child with a developmental disability. J. Policy Pract. Intellect. Disabil. 2006, 3, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tait, K.; Fung, F.; Hu, A.; Sweller, N.; Wang, W. Understanding Hong Kong chinese families' experiences of an autism/ASD diagnosis. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2016, 46, 1164–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejada-Ortigosa, E.Thou.; Flores-Rojas, Thou.; Moreno-Quintana, L.; Muñoz-Villanueva, Thou.C.; Pérez-Navero, J.L.; Gil-Campos, Thousand. Health and socio-educational needs of the families and children with rare metabolic diseases: Qualitative report in a 3rd hospital. An. Pediatr. 2019, ninety, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holloway, S.D.; Dominguez-Pareto, I.; Cohen, S.R.; Kuppermann, M. Whose job is it? Everyday routines and quality of life in latino and non-latino families of children with intellectual disabilities. J. Ment. Health Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2014, seven, 104–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algood, C.; Davis, A.M. Inequities in family quality of life for african-american families raising children with disabilities. Soc. Work Public Health 2019, 34, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Summers, J.A.; Fiddling, T.; Turnbull, A.; Poston, D.; Mannan, H. Perspectives of fathers and mothers of children in early intervention programmes in assessing Family Quality of Life. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2006, 50, 977–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyson, T.; Roeyers, H. The overall quality of my life as a sibling is all right, but of course, it could always be better'. Quality of Life of siblings of children with intellectual inability: The siblings' perspectives. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2012, 56, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steel, R.; Poppe, 50.; Vandevelde, Southward.; Van Hove, G.; Claes, C. Family Quality of Life in 25 belgian families: Quantitative and qualitative exploration of social and professional back up domains. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2011, 55, 1123–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hielkema, T.; Boxum, A.Grand.; Hamer, East.Thousand.; La Bastide-Van Gemert, S.; Dirks, T.; Reinders-Messelink, H.A.; Maathuis, C.G.B.; Verheijden, J.; Geertzen, J.H.B.; Hadders-Algra, M. LEARN2MOVE 0–2 years, a randomized early intervention trial for infants at very high risk of cerebral palsy: Family outcome and infant's functional outcome. Disabil. Rehabil. 2019, 41, 1–nine. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samuel, P.Southward.; Hobden, Grand.L.; Leroy, B.W.; Lacey, One thousand.1000. Analysing family service needs of typically underserved families in the Usa. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2012, 56, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Summers, J.A.; Marquis, J.; Mannan, H.; Turnbull, A.P.; Fleming, Thousand.; Poston, D.J.; Wang, M.; Kupzyk, One thousand. Relationship of perceived adequacy of services, family-professional person partnerships, and Family Quality of Life in early on childhood service programmes. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2007, 54, 319–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcells-Balcells, A.; Gine, C.; Guardia-Olmos, J.; Summers, J.A.; Mas, J.Chiliad. Impact of supports and partnership on Family Quality of Life. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2019, 85, 50–threescore. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, Y.-J.; Higgins, G.; Pierce, T.; Whitby, P.J.S.; Tandy, R.D. Parental stress, family quality of life, and family-teacher partnerships: Families of children with autism spectrum disorder. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2017, 70, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, K.; Gavidia-Payne, S. The affect of kid, family unit, and professional person support characteristics on the Quality of Life in families of immature children with disabilities. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2009, 34, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meral, B.F.; Cavkaytar, A.; Turnbull, A.P.; Wang, Yard. Family Quality of Life of turkish families who take children with intellectual disabilities and autism. Res. Pract. Pers. Sev. Disabil. 2013, 38, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svavarsdottir, E.K.; Tryggvadottir, 1000.B. Predictors of Quality of Life for families of children and adolescents with severe physical illnesses who are receiving hospital-based care. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2019, 33, 698–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, Y.-J. Autism Spectrum Disorders: Family unit demographics, parental stress, and Family Quality of Life. J. Policy Pract. Intellect. Disabil. 2018, 15, seventy–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Thou.; Turnbull, A.P.; Summers, J.A.; Niggling, T.D.; Poston, D.J.; Marman, H.; Turnbull, R. Severity of disability and income as predictors of parents' satisfaction with their family quality of life during early childhood years. Res. Pract. Pers. Sev. Disabil. 2004, 29, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehm, T.Fifty.; Carter, E.W. Family Quality of Life and its correlates among parents of children and adults with intellectual disability. Am. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2019, 124, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyzar, One thousand.; Brady, S.; Summers, J.A.; Turnbull, A. Family Quality of Life and partnership for families of students with deaf-blindness. Remedial Spec. Educ. 2018, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinger, M.; Alhuzail, N.A. Bedouin hearing parents of children with hearing loss: Stress, coping, and Quality of Life. Am. Ann. Deaf 2018, 163, 328–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlebusch, L.; Samuels, A.E.; Dada, S. South african families raising children with Autism Spectrum Disorders: Relationship betwixt family routines, cognitive appraisal and Family unit Quality of Life. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2016, lx, 412–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turnbull, A.P.; Summers, J.A.; Lee, S.-H.; Kyzar, K. Conceptualization and measurement of family outcomes associated with families of individuals with intellectual disabilities. Ment. Retard. Dev. Disabil. Res. Rev. 2007, 13, 346–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schippers, A.; Zuna, Northward.; Dark-brown, I. A Proposed framework for an integrated procedure of improving quality of life. J. Policy. Pract. Intellect Dis. 2015, 12, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boelsma, F.; Caubo-Damen, I.; Schippers, A.; Dane, M.; Abma, T.A. Rethinking FQoL: The dynamic interplay between private and Family Quality of Life. J. Policy Pract. Intellect. Disabil. 2017, fourteen, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, E.; Iarocci, Thousand. Family unit Quality of Life and ASD: The function of child adaptive functioning and behavior bug. Autism Res. 2015, 8, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Heumen, L.; Schippers, A. Quality of Life for immature adults with intellectual disability post-obit individualised support: Private and family responses. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2016, 41, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, D.; Brown, I. Social and Cultural Considerations in Family Quality of Life: Jewish and Arab Israeli Families' Child-Raising Experiences. J. Policy Pract. Intellect. Disabil. 2017, 14, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luijkx, J.; van der Putten, A.A.J.; Vlaskamp, C. "I love my sister, but sometimes I don't": A qualitative study into the experiences of siblings of a child with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2016, 41, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feigin, R.; Barnetz, Z.; Davidson-Arad, B. Quality of Life in family members coping with chronic illness in a relative: An exploratory report. Fam. Syst. Health 2008, 25, 267–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, 1000.; Mannan, H.; Poston, D.; Turnbull, A.P.; Summers, J.A. Parents' Perceptions of advocacy activities and their impact on Family Quality of Life. Res. Pract. Pers. Sev. Disabil. 2004, 29, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z. The Quality of Family unit Life and lifestyle. In The Chinese Family Today; Xu, A., Defrain, J., Liu, W., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2016; Volume vii, pp. 248–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderkerken, L.; Heyvaert, K.; Onghena, P.; Maes, B. Mother Quality of Life or Family Quality of Life? A survey on the Quality of Life in families with children with intellectual disabilities using home-based support in Flemish region. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2016, 60, 756. [Google Scholar]

Effigy one. Flowchart of the pick procedure co-ordinate to the recommendations of the Prisma argument. (Moher and Liberati [26]). Source: Own elaboration.

Figure 1. Flowchart of the selection process co-ordinate to the recommendations of the Prisma argument. (Moher and Liberati [26]). Source: Own elaboration.

Table 1. Search procedures for English and Castilian publication.

Tabular array 1. Search procedures for English language and Spanish publication.

| Plataform | Results | Search | Languages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scopus | 563 | "Family Quality of Life" OR "Quality of Family Life" | English |

| nine | "Calidad de Vida Familiar" | Spanish | |

| WOS | 416 | "Family unit Quality of Life" OR "Quality of Family Life" | English |

| 20 | "Calidad de Vida Familiar" | Spanish | |

| Eric | 107 | "Family unit Quality of Life" OR "Quality of Family Life" | English |

| iv | "Calidad de Vida Familiar" | Castilian | |

| Total | 1119 |

Table 2. Theoretical conceptualization of FQoL.

Table 2. Theoretical conceptualization of FQoL.

| Definitions of Family Quality of Life | Articles |

|---|---|

| Weather where the family'south needs are met, and family members savor their life together as a family and have the chance to do things which are of import to them. | Turnbull et al. [22] Cited past Park et al. [28] (pp. 368) |

| It can exist said that families feel a satisfactory quality of family life when: (a) they achieve what families around the world, and they in detail, strive to achieve; (b) they are satisfied with what families around the earth, and they in particular, have achieved; (c) they experience empowered to live the lives they wish to live. | Brown and Brown [xx] (pp. 32) |

| Family quality of life is a dynamic sense of well-being of the family unit, collectively and subjectively defined and informed by its members, in which individual and family-level needs collaborate. | Zuna et al. [16] (pp. 262) |

| Family quality of life is concerned with the degree to which individuals experience their ain quality of life inside the family context, equally well as with how the family equally a whole has opportunities to pursue its important possibilities and achieve its goals in the community and the social club of which it is a function. | Chocolate-brown and Chocolate-brown [21] (pp. 2195) |

Table three. Conceptualization of FQoL across half-dozen researcher groups.

Table 3. Conceptualization of FQoL across six researcher groups.

| Beach Center FQoL scale (Hoffman et al. [18]) 5 Domains | FQoLsurvey-2006 International Project (Dark-brown et al. [17]) 9 Domains | FQoL-S (Giné et al. [xix]) 7 Domains | The Autism Family unit Experience Questionnaire (AFEQ) (Leadbiter et al. [29]) 4 Domains | ITP-Child Quality-of-Life Questionnaire (Barnard et al. [thirty]) 5 Domains | Feiqol-Family Early Intervention Quality of Life (Garcia-Grau et al. [24]) 3 Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| one. Family Interaction 2. Parenting 3. Emotional Well-being iv. Concrete-Well-being material 5. Inability Related Back up | 1. Health 2. Finances 3. Family Relationships four. Informal Back up five. Service Support 6. Influence of values 7. Career path 8. Leisure and free fourth dimension 9. Customs | 1. Emotional well-beingness 2. Family unit Interaction 3. Wellness 4. Terminal well-being v. Arrangement and parenting skills 6. Accomodation of the family vii. Social Inclusion and Participation | ane. Parents 2. Family unit three. Kid development four. Child symptoms | 1. Treatment side event-related 2. Intervention related 3. Illness-related 4.Activity-related 5. Family-related | one. Family Relationships 2. Admission to Information and Services 3. Child Operation |

Table iv. FQoL instruments in the 0- to 6-year stage.

Table four. FQoL instruments in the 0- to half-dozen-year stage.

| Instruments and Authors | Answer | Domains | Dimensions | Number of Items and Reliability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Autism Family unit Experience Questionnaire (AFEQ) (Leadbiter et al. [29]) | Parents | 4 domains: (1) Parents; (two)Family; (3) Child development; (4) Child symptoms | Likert Scale of frequency ane to five points (with "non applicative" choice) | 56 items |

| ITP-Child Quality-of-Life Questionnaire (Barnard et al. [30]) | Parents | v domains: (one) treatment side effect-related; (2) intervention related; (3) disease-related; (four) activeness-related; and (five) family unit-related | Likert scale of frequency and importance 1 to 5 points | 26 items |

| Family Early on Intervention Quality of Life (FEIQoL) García Grau et al. [24] * | three Factors: (i) Family unit Relationships; (ii) Access to Information and Services; (3) Child Operation | Likert Scale one to 5 points of "poor" to "excellent" | xl items |

Table 5. Studies that adapt, develop or validate the FQoL scales.

Table 5. Studies that arrange, develop or validate the FQoL scales.

| Scales | Evolution, Validation or Adaptation Studies | Country |

|---|---|---|

| Embankment Center FQoL Calibration (Hoffman et al., 2006) [18] | Balcells-Balcells et al., 2011 [39]; Verdugo et al., 2005 [52] | Espana |

| Chiu et al., 2017 [40]; Chiu et al., 2017 [53] | Hong Kong | |

| Waschl et al., 2019 [54] | Singapore | |

| Bello-Escamilla et al., 2017 [55]; | Chile | |

| Rivard et al., 2017 [56] | Canada | |

| FQOL Survey-2006 (Brown et al., 2006) [17] | Perry eastward Isaacs 2015 [57]; Samuel et al., 2016 [fifteen]; Samuel et al., 2018 [58] | USA |

Table vi. Descriptive, comparative or correlational studies.

Table half-dozen. Descriptive, comparative or correlational studies.

| Theme | Authors (Year) (Chronological Social club) |

|---|---|

| Population | Córdoba et al., 2008 [59]; Neikrug et al., 2011 [60]; Clark et al., 2012 [61]; Rillotta et al., 2012 [35]; Giné et al., 2015 [62]; Mas et al., 2016 [6]; Schertz et al., 2016 [32]; García Grau et al., 2018 [44]; Rodrigues et al., 2018 [63]. |

| Maternal Outcomes | McStay et al., 2014 [64,65]. |

| Blazon of disability | Brown et al., 2006 [66]; Jackson et al., 2010 [48]; Schertz et al., 2016 [32]; Tait et al., 2016 [67]; Schlebusch et al., 2017 [37]; Tejada-Ortigosa et al., 2019 [68]. |

| Ethnic perspective | Holloway et al., 2014 [69]; Algood and Davis, 2019 [70]. |

| Attention to participants | Wang et al., 2006 [71]; Moyson and Roeyers, 2012 [72]. |

| Supports | Steel et al., 2011 [73]; Escorcia-Mora et al., 2018 [25]. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Source: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/17/19/7220/htm

0 Response to "A Type of Family Strength According to Defrain and Assay (2007):"

Postar um comentário